Un piccolo verme ci spiega perché invecchiamo / A small worm explains because we age

Un piccolo verme ci spiega perché invecchiamo / A small worm explains because we age

Segnalato dal Dott. Giuseppe Cotellessa / Reported by Dr. Giuseppe Cotellessa

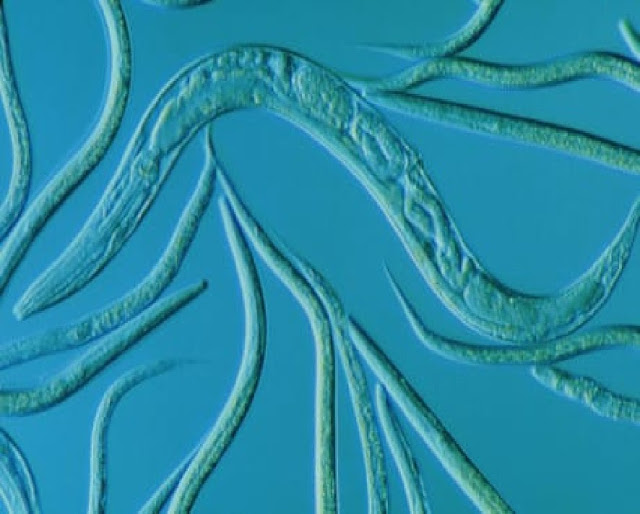

Microfotografia di C. elegans. / C. elegans microphotography.

I geni che controllano l'autofagia, grazie alla quale le cellule si liberano delle scorie, hanno una notevole influenza anche sulla longevità. Il risultato è emerso da uno studio sul verme C. elegans e potrebbe essere importante anche per la specie umana.

Perché invecchiamo? La domanda potrebbe sembrare ingenua, e qualche biologo o qualche medico potrebbe abbozzare una risposta, spiegando i processi che fanno sì che tessuti, organi e apparati del corpo umano non possano rimanere sempre uguali e sempre in efficienza con il passare degli anni.

Una risposta più circostanziata e più approfondita potrebbe darla ora un gruppo di ricercatori dell’Istituto di biologia molecolare (IMB) di Mainz, in Germania, e illustrato sulle pagine della rivista “Genes & Development”. Studiando il verme Caenorhabditis elegans, uno dei modelli animali più usati in biologia, gli studiosi, guidati da Holger Richly, hanno dimostrato che a promuovere lo stato di salute nei giovani vermi, ma anche il loro invecchiamento, sono alcuni geni coinvolti nell'autofagia, l'insieme dei meccanismi che consentono il ricambio dei componenti del citoplasma cellulare e la rimozione degli organelli non più funzionali o danneggiati. L'autofagia è cruciale per il corretto svolgimento di un intero ciclo di vita cellulare, quindi è uno dei processi più critici per la sopravvivenza delle cellule.

Una risposta più circostanziata e più approfondita potrebbe darla ora un gruppo di ricercatori dell’Istituto di biologia molecolare (IMB) di Mainz, in Germania, e illustrato sulle pagine della rivista “Genes & Development”. Studiando il verme Caenorhabditis elegans, uno dei modelli animali più usati in biologia, gli studiosi, guidati da Holger Richly, hanno dimostrato che a promuovere lo stato di salute nei giovani vermi, ma anche il loro invecchiamento, sono alcuni geni coinvolti nell'autofagia, l'insieme dei meccanismi che consentono il ricambio dei componenti del citoplasma cellulare e la rimozione degli organelli non più funzionali o danneggiati. L'autofagia è cruciale per il corretto svolgimento di un intero ciclo di vita cellulare, quindi è uno dei processi più critici per la sopravvivenza delle cellule.

Il risultato è rilevante innanzitutto perchè mette un punto fermo in un annoso dibattito tra gli evoluzionisti. Secondo la teoria darwiniana dell’evoluzione, la selezione naturale opera in favore dei tratti di un individuo che conferiscono un miglior adattamento all’ambiente, e quindi una maggiore probabilità di sopravvivenza fino all’età riproduttiva. In definitiva, il risultato è la propagazione dei geni che sono alla base di questi tratti nella progenie. Quanto più un tratto è utile nel promuovere il successo riproduttivo, tanto più è forte la selezione a favore di quel tratto.

Ora,

in teoria il meccanismo della selezione naturale dovrebbe favorire anche tratti che ritardano l’invecchiamento, e i geni relativi dovrebbero propagarsi in modo pressoché continuo alle generazioni successive. Invece, con tutta evidenza questo non avviene.

La questione è stata sollevata fin dal XIX secolo, ma solo nel 1953, grazie all’opera del biologo statunitense George C. Williams, che formulò l’ipotesi dalla pleiotropia antagonistica. In sostanza, secondo questa ipotesi ci possono essere geni che hanno più di un effetto sulla vita di un individuo. E se un gene favorisce la riproduzione ma è negativo per l’età post-riproduttiva, per esempio diminuisce la longevità, si propagherà senza problemi. In altre parole, all’evoluzione non importa nulla di ciò che succede nella maturità e nella vecchiaia di un essere vivente. Dopo miliardi di anni di evoluzione, il risultato è che i processi d’invecchiamento hanno messo profonde radici nel nostro DNA.

La teoria della pleiotropia antagonistica è stata verificata con modelli matematici e le sue conseguenze sono ben documentate nel mondo reale. L’unica cosa che mancava finora era una prova dell’esistenza di questo tipo di geni.

Questa prova mancante è stata ora fornita dall’autofagia. Richly e colleghi sono partiti dalla constatazione che in C. elegans, l’autofagia rallenta con l’età fino a deteriorarsi completamente nella vecchiaia. Grazie al loro studio, non solo hanno individuato i geni coinvolti nell’autofagia, ma hanno dimostrato anche che silenziandoli si ottiene un miglioramento notevole dello stato di salute dei vermi studiati e un incremento della loro sopravvivenza.

In prospettiva, le conseguenze di questo risultato potrebbero essere di grande portata per la salute umana.

“Molte malattie neurodegenerative, tra cui Alzheimer, Parkinson e corea di Huntington sono associate a un cattivo funzionamento dell’autofagia”, ha spiegato Jonathan Byrne, coautore dello studio. “È quindi possibile che questi geni per l’autofagia possano essere un buon modo per preservare l’integrità neuronale in questi casi”.

Ora,

La questione è stata sollevata fin dal XIX secolo, ma solo nel 1953, grazie all’opera del biologo statunitense George C. Williams, che formulò l’ipotesi dalla pleiotropia antagonistica. In sostanza, secondo questa ipotesi ci possono essere geni che hanno più di un effetto sulla vita di un individuo. E se un gene favorisce la riproduzione ma è negativo per l’età post-riproduttiva, per esempio diminuisce la longevità, si propagherà senza problemi. In altre parole, all’evoluzione non importa nulla di ciò che succede nella maturità e nella vecchiaia di un essere vivente. Dopo miliardi di anni di evoluzione, il risultato è che i processi d’invecchiamento hanno messo profonde radici nel nostro DNA.

La teoria della pleiotropia antagonistica è stata verificata con modelli matematici e le sue conseguenze sono ben documentate nel mondo reale. L’unica cosa che mancava finora era una prova dell’esistenza di questo tipo di geni.

Questa prova mancante è stata ora fornita dall’autofagia. Richly e colleghi sono partiti dalla constatazione che in C. elegans, l’autofagia rallenta con l’età fino a deteriorarsi completamente nella vecchiaia. Grazie al loro studio, non solo hanno individuato i geni coinvolti nell’autofagia, ma hanno dimostrato anche che silenziandoli si ottiene un miglioramento notevole dello stato di salute dei vermi studiati e un incremento della loro sopravvivenza.

In prospettiva, le conseguenze di questo risultato potrebbero essere di grande portata per la salute umana.

“Molte malattie neurodegenerative, tra cui Alzheimer, Parkinson e corea di Huntington sono associate a un cattivo funzionamento dell’autofagia”, ha spiegato Jonathan Byrne, coautore dello studio. “È quindi possibile che questi geni per l’autofagia possano essere un buon modo per preservare l’integrità neuronale in questi casi”.

ENGLISH

The genes that control autophagy, by which cells release slags, also have a significant influence on longevity. The result emerged from a study on the C. elegans worm and could also be important for the human species.

Why do we grow old? The question may seem naive, and some biologists or some physician could sketch an answer, explaining the processes that make tissues, organs, and apparatus of the human body not always remain equal and always in efficiency over the years.

A more detailed and deeper answer could now be given by a group of researchers from the Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB) in Mainz, Germany, and illustrated on the pages of the magazine "Genes & Development". By studying the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, one of the most widely used animal models in biology, scholars, led by Holger Richly, have shown that promoting some health status in young worms but also their aging are some genes involved in autophagy, the set of mechanisms that allow the replacement of the components of the cell cytoplasm and the removal of organelles no longer functional or damaged. Autophagy is crucial to the proper running of a whole cell cycle, so it is one of the most critical processes for the survival of cells.

The result is important first of all because it puts a stop to a long-lived debate among evolutionists. According to Darwinian theory of evolution, natural selection works in favor of the traits of an individual that give a better adaptation to the environment, and thus a greater chance of survival up to the reproductive age. Ultimately, the result is the propagation of the genes that are the basis of these traits in the progeny. The more a stretch is useful in promoting reproductive success, the stronger the selection in favor of that stretch.

Now, in theory, the mechanism of natural selection should also favor traits that delay aging, and related genes should propagate almost continuously to subsequent generations. Instead, it does not really matter.

The issue has been raised since the nineteenth century, but only in 1953, thanks to the work of US biologist George C. Williams, who formulated the hypothesis of antagonistic pleiotropy. In essence, according to this hypothesis there may be genes that have more than one effect on an individual's life. And if a gene favors reproduction but is negative for the post-reproductive age, for example, it decreases longevity, it will propagate without problems. In other words, evolution does not matter anything about what is happening in the maturity and old age of a living being. After billions of years of evolution, the result is that aging processes have deep roots in our DNA.

The theory of antagonistic pleiotropy has been verified with mathematical models and its consequences are well documented in the real world. The only thing missing so far was a test of the existence of this kind of genes.

This lack of evidence has now been provided by the self-care. Richly and colleagues started from the finding that in C. elegans, autophagy slows down with age until completely aging in old age. Thanks to their study, they have not only identified the genes involved in autophagy but have also shown that by silencing them, a significant improvement in the health of worms studied and an increase in their survival are obtained.

In the prospect, the consequences of this result could be of great benefit to human health.

"Many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's Chorea, are associated with a malfunction of autophagy," said Jonathan Byrne, co-author of the study. "It is, therefore, possible that these genes for autophagy can be a good way to preserve neuronal integrity in these cases."

Da:

http://www.lescienze.it/news/2017/09/21/news/geni_autofagia_invecchiamento-3671018/

Commenti

Posta un commento